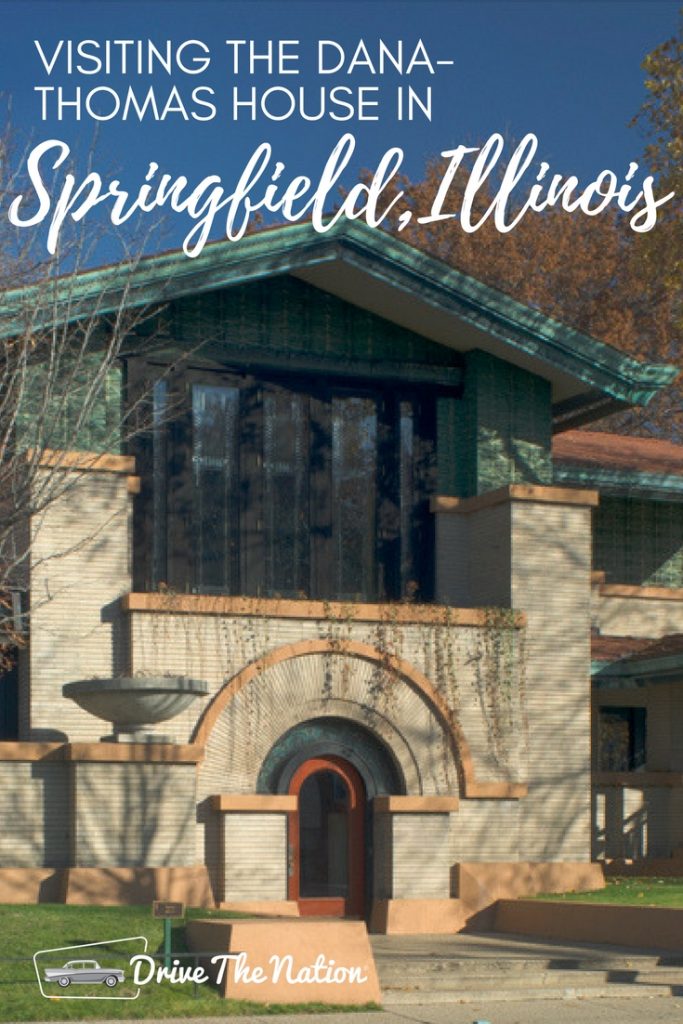

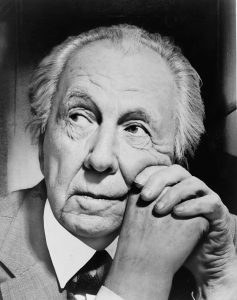

Springfield, Illinois is famous for two fabulous reasons. The first is Abraham Lincoln, who practiced law there, and left the city to become President. You can tour his home in the four-block park in which it stands, and see other Lincoln-related sites. He is buried in Springfield in a monumental tomb, which rivals the Lincoln Memorial in inspirational solemnity. The second is, Springfield is also the home to the Dana-Thomas House, one of world-renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s finest early works. You can tour the home and see Wright’s intricate and comprehensive vision for living well.

Susan Lawrence Dana

Completed in 1904, the house was conceived as a place of gracious entertainment and modern comfort, commissioned by the redoubtable Susan Lawrence Dana. Mrs. Dana was the doyenne of Springfield society in that era, and her home was the center for high-toned evenings.

The concept was to preserve and build around the square Italianate house that Mrs. Dana had grown up in. This idea was presented to Wright, but as he often did, Wright went one step further. He more or less obliterated the old house, in creating the new one. A vestige of it remains, a rather anachronistic Victorian parlor, in the hidden recesses of the house. All around it is the 12,000 square feet of the new house, with its more than 100 pieces of furniture, and 450 art glass windows, doors and light fixtures, all designed by Wright. The house features low hip roofs, broad overhanging eaves, sheltered alcoves, interior fountains, and stairways leading to unexpectedly grand spaces, all in tones of the Illinois autumn prairie.

Take a Tour

Tours begin in the well-appointed visitor center and gift shop, created out of the original carriage house/garage. This is tucked into the back of the property, on the far side of the extensive walled garden. You will want to return to the gift shop after the tour. There, you will find some one-of-a-kind treasures to take home with you. And you can also take a selfie with the life-size photo of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Your guide will take you into the house after a stroll along one side of it where you will see details of the exterior architecture that are characteristic of Wright’s work. Keep in mind that his concept of the Prairie Home was still emerging, and finding its full expression. He gave his imagination free reign here.

One enters the home by way of a door surrounded by stained glass in the stylized design of butterflies. The view of the house at the entry shows Wright’s sense of space, which is not symmetrical but rather balanced. The large urn to the left of the front door is a signature feature of this and many of Wrights prairie era houses. From the sidewalk you can see the sweep of the house to the left, with the long pavilion connecting the main house to the Gallery.

Interior

Entry

In the entry, you can peer into the upper and lower floors, as you ascend to the main floor by one of the pair of staircases. You can also admire the Richard Bock statue, entitled “Flower in the Crannied Wall, with its Wright-designed fanciful skyscraper. You will notice that the lighting in the home is dim. This is to reproduce the level of lighting that would have been in the home originally, as well as to preserve the interiors from undue fading. As authentic and practical as this is, it does make seeing the interiors a bit of a challenge. Take time to allow your eyes to adjust. In each room, be sure to focus on the details you find there.

At the top of the stairway, the reception room fireplace serves as the symbolic and actual heart of the home. Wright believed that gathering around the fire was the center of family and home life. There are other fireplaces in the home that serve a similar function. To your left as you are\rive on this floor is a Richard Bock and Marion Mahoney designed fountain.

Main Floor

The tour of the main floor includes the living room and the barrel vaulted dining room. The dining room also features murals by Wright associate George Mann Niedecken, displaying the flora of an early autumn Illinois prairie. Be sure to look at the pottery displayed in the glass fronted cases as well as scattered around the house, all of it museum quality pottery from one hundred years ago by makers like Teco, Grueby, Rookwood, Van Briggle, Weller, Zanesville Stoneware, Fulper, and Peters and Reed.

Light Screens

Notice the stylized sumac leaded glass windows which Wright called light screens. These not only provided a splendid decorative motif to the home, they also lent privacy, since the panes, from the exterior, reflected light. For those inside, the view was unobstructed by reflections.

No Ordinary Home

Modern eyes may find the house a bit fussy, but in 1904, this was a radically simpler interior design scheme than one would have found in conventional homes. The master bedroom displays interior curtains that could be drawn to compartmentalize the space visually and to prevent drafts. Down in the basement there is a blowing alley, coatracks for hundreds of guests, and a vault for valuables, reminding you (if you needed such a reminder), that this was no ordinary home.

The Thomases

Susan Lawrence Dana owned this, the best preserved and most complete of Wright’s early prairie houses, until 1944. Then, it was purchased by Mr. and Mrs. Charles C. Thomas for their publishing firm. They were Wright admirers, so kept much of the furniture, glass, and woodwork as Wright designed it. When it was bought by the State of Illinois in 1981, the house went through a three-year thorough restoration.

For more information about dates and times to visit, check out the Dana-Thomas House website. If you will be visiting from out of town, take a look at these hotel deals from our sister site, HotelCoupons.com.